Alexie Sommer, Director of Communications for Thomas.Matthews, recounts her experience volunteering for a beach clean up in Hawaii.

What a dream – a winter break to Hawaii! The Pacific islands of paradise, home to hula, surfing, life on the ocean, legends of Captain Cook and the birthplace of Barack Obama. I couldn’t imagine a better way to bring in 2013 than basking in the sun as VIPs at the Waimea Ocean Film Festival. A brilliant boutique festival dedicated to films about the Ocean and clever enough to accept my other half’s wonderful film ‘Step n Soul’.

Sophie Thomas encouraged me to investigate Kamilo beach while I was there. Located on the very south point of Hawaii Big Island, this beach is known for its accumulation of plastic marine debris. Kamilo means ‘twisting or swirling currents’ in Hawaiian and historically was the place to go to find evergreen logs to make canoes. It has since developed into one of our ocean’s dirtiest secrets.

The source of this debris is the Pacific Garbage Patch. This horrific man-made phenomenon first appeared on my radar in 2007, whilst helping David de Rothschild brainstorm his Plastiki mission. In 2010 David and crew sailed across the North Pacific Gyre in a boat made entirely from plastic bottles to raise awareness about this floating rubbish dump. The Pacific Garbage Patch, is now twice the size of Texas, and growing everyday. I have so many questions:

How did it get there? What sort of garbage is it? And why don’t governments just send out trawlers and clean it up? My visit to Hawaii meant I might be able to start answering some of these questions first-hand.

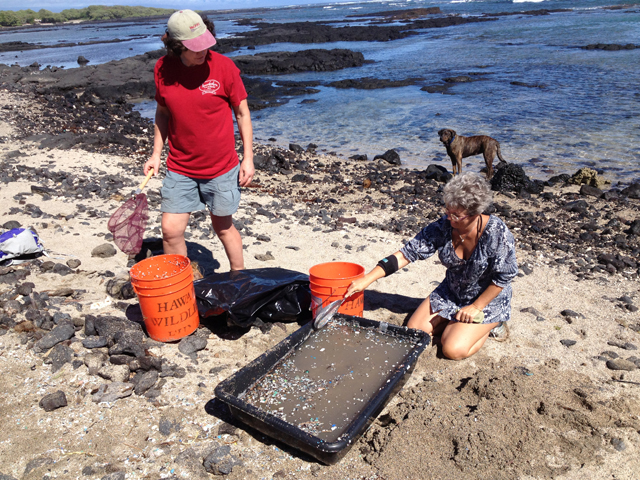

Research led me to Hawai’i Wildlife Fund, an NGO dedicated to the preservation of Hawaii’s native wildlife through research, education and conservation. By pure chance a beach clean up at Kamilo point was scheduled for our last day of holiday. It was a tough call between one more day snorkelling, or a 4:50am start (ouch!) to clean up a beach. Intrigue meant the dirty beach won.

Volunteers of all shapes and sizes had made it to Wai‘ōhinu Park for the early start, including a group of fifteen scientists from Japan who were amongst the fifty strong pairs of helpful hands. The drive to Kamilo point is a rough 2 hour off-road through green pastures that turn into gnarly volcanic terrain. A beautiful spot: remote and wild with little sign of people, just beach.

We jumped out of the trucks and instantly saw the plastic, the beach was covered in it. There is plastic debris everywhere at Kamilo. Large to miniscule: packaging, bottles of all sizes and uses, fishing nets, tyres, old fridges, soles of shoes, oyster spacers, polystyrene blocks, pen and bottle lids, lobster catchers, printer ink cartridges, toothbrushes, lighters, hooks, crooks and everything in between…

The sight is horrifying and captivating. Horrifying because I know our group only has a few hours with so much work to do. It’s such an instant and physical education as to how much damage we’re really doing to the oceans. Captivating because the plastic is every colour under the sun and has been weathered by months or years at sea. Like hunting for sea glass as a child, it brings back the same emotions of finding treasure. Yet this is toxic treasure.

We get to work with gloves, buckets and sharp eyes, the midday sun is beating down and it’s slow progress. After a few hours cleaning up endless pieces of surface plastic, I take a walk. At the water’s edge I notice floating bits. On closer inspection it’s like plastic soup, and the rocks are covered in it. Tiny plastic pebbles, some as small as the sand itself, practically impossible to separate and remove. The scale of work needed to truly clean the beach is overwhelming. We keep on plodding.

After five hours of hard graft, it’s time to pack up and ship out. Five tonnes of debris collected yet the beach looks like we haven’t even started! The plastic is transported to an energy-from-waste plant, the rest goes to landfill. A bleak reminder that there is no, ‘away’. At least our collected pieces are temporarily not in direct contact with ocean nature and decomposing every second.

Some of the plastic I picked up on the beach was falling apart in my hands – an instant physical clue as to how plastic is infiltrating our ocean’s ecosystem. Buckets are decomposing creating plastic Plankton, it is literally choking the wildlife. Stories of marine animals dying from consuming plastic are becoming more and more regular. Heart-breaking evidence will be seen in Chris Jordan’s new film ‘Midway’, funded by kickstarter. It will tell the story of the Albatross’s plight feeding on colourful plastic debris mistaken for food.

We have got it so wrong. No-one seems to be doing enough to effectively combat this problem on a large scale, but thankfully there are some fantastic awareness projects out there. RCA graduates Kieren Jones, Alexander Groves and Azusa Murakami have created The Sea Chair Project, and are in the process of turning a retired fishing trawler into a plastic chair factory, which uses plastic harvested from the sea to make recycled chairs.

Interface, the innovative carpet company, have teamed up with the Zoological Society of London to create ‘Net-Works’ a social project in the Phillipines that is making carpet tiles from discarded fishing nets. Ecover is working with plastic Manufacturer Logoplaste to create an entirely new type of plastic bottle from plastic waste retrieved from the sea. All good steps in the right direction.

Instinct says there’s money in this ocean waste if only we could harvest it quickly and efficiently. The tiny fragments of plastic are impossible to collect, and it would take thousands of lifetimes. If only someone could invent a plastic magnet that works in salt water environments. Come on scientists? With a plastic magnet, beach clean ups would be a breeze.

Thomas.Matthews is a communication design studio based in London. They create delightful considered solutions for spaces and social change. Amongst an array of fantastic projects they designed the identity for the Great Recovery.