Resources - Blog

Haute Clutture

“People are being persuaded to spend money we don’t have, on things we don’t need, to create impressions that won’t last, on people we don’t care about” Tim Jackson, TED

I have been watching a series of films made by the Culture, Materials & Design Anthropology students at UCL for a brief set by The Great Recovery around people’s personal ‘stuff’.

Their footage follows a middle aged married couple in their home in South London (above) juxtaposed with another film of a young professional living in a newly built shared apartment in Notting Hill. The students were quizzing the inhabitants about their possessions. The shot pans around the house in South London, which is piled high with stuff; intricately carved wooden heads from Africa, stuffed toy animals, audio equipment with its vast quantity of snaking wires, CDs, books and trinkets. Kitchen drawers opened exposing a myriad of objects deemed ‘too useful’ to throw away. One of the couple starts to talk: “I don’t have anything in my house that is not useful to me, I don’t like objects that have no particular function”.

In the second film we pan around the stark white walled room belonging to a young advertising professional. Objects have been carefully curated on the shelves; an unopened beer can; a bottle of whiskey; a vintage camera. All these objects relate to specific moments, reflecting history through their creases and scuffs, and held in a personal space. A stark contradiction when we pan through to the small shared kitchen where chaos rules. Piles of food packaging flows from the bins and the shared fridge is smaller than a bathroom cabinet.

Watching these films made me realise three things:

1. The way I define usefulness is not universal.

I could see no intrinsic use in most of the stuff that populated the first house – but the couple who lived there clearly did. As a designer this is a very interesting concept. Can a trinket carrying personal memories be deemed useful? People’s possessions are testimonies to their history and not everything has to be practical. We seem to be very good at building attachment to our objects. We like to customize our things, and we define ourselves through the brands we have around us. Brands use this desire to build entire campaigns enticing us to identify with their lifestyle and therefore buy whatever they are selling – its clever stuff.

2. Many newly built houses are not fit for purpose.

The 3-bedroom apartment in Notting Hill was a new development. It’s built-in kitchen was not, it seemed, designed to cook in; its fridge was so small it had no room for fresh vegetables and and there was a tiny amount of preparation space on the counters.

RIBA’s report ‘The Case for Space: The Size of England’s new homes‘ highlights that the average 1 bedroom home newly built in the UK is 4sqm short of the recommended minimum size. It puts this into perspective by relating it to our use of space; 4 sqm is enough to work at home on a computer comfortably or ample room for a single bed with a bedside table and a dressing table with a stool. 57% of the people they surveyed said they did not have enough storage for their possessions and 35% said they did not have enough space for their kitchen appliances.

3. Designers can’t predict the user experience.

Finally, the question I had posed to the students was giving different answers to that which I had expected. I had asked them to observe people’s disposal habits, but the films clearly showed how bad we seem to be at this, generally keeping things for as long as possible to the point where we border on hoarding. In fact the UK is seeing a rise in extreme hoarding and we now have dedicated helplines for those that suffer.

Even though I am nowhere near extreme, I have a clutter drawer where all manner of things are shoved out of sight. Things I don’t know where to put but can’t yet face to throw away end up there. It’s where my old mobile phones live side by side with forgotten plastic toys from kid’s party bags, old batteries and pens that no longer work. When I open this drawer I despair in the same way one woman in the films despaired when she went up into her loft and saw the boxes of unopened possessions still carefully packed from a move two years ago. It was so much easier to close the door and walk away.

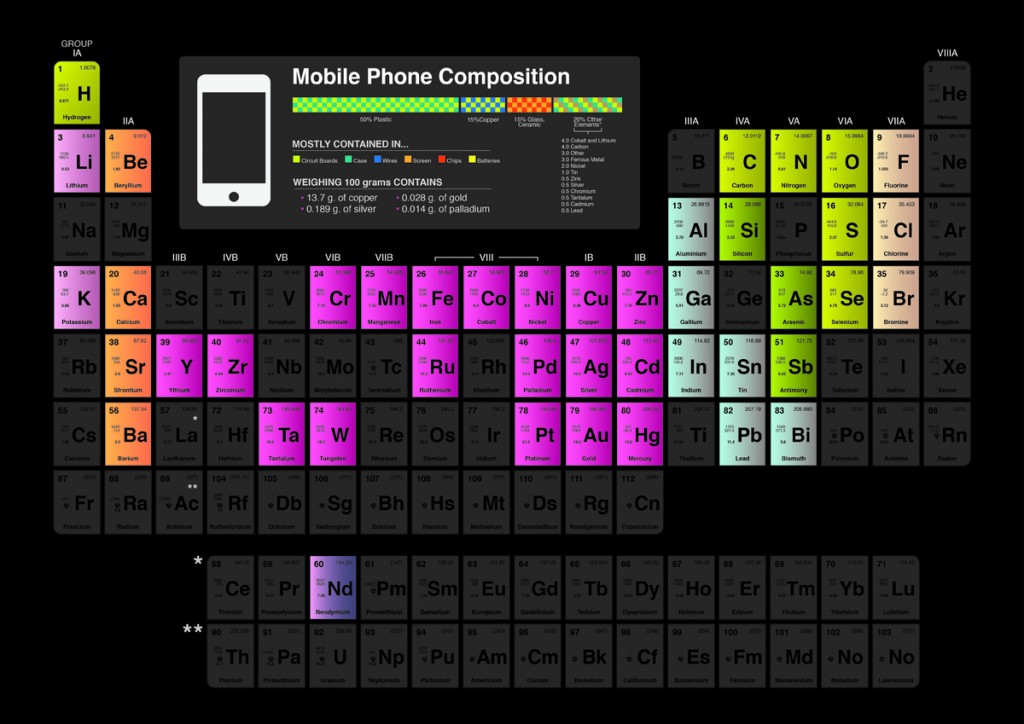

Our hoarding habits are beginning to become an issue: We are squirreling away valuable resources. Research done by Hallam University as part of their ‘What’s in my stuff‘ project estimates that the UK have over 85 million old mobile phones stuffed into those drawers. We pull out excuses that we don’t know where to send them, still hold useful addresses/pictures/fond memories in them or keep them for our kids to play with. Each phone is made of approximately 40 different elements including Copper in the wiring, Indium in the touch screen and Gold in the circuit boards. These elements are becoming increasingly viable to recover as the price of metals and minerals increase. There is more gold in a ton of mobile phones (approx. 300g) than there is in a ton of mined rock from a gold mine (approx. 1 – 5g)

Our clutter drawers are filling up fast. It seems it much easier to design things without talking to the people who have to live with the stuff and eventually dispose of it and with little or no consideration as to where our finished products will end up: re-used, recovered or landfilled once we as consumers are finished with them.

Incredibly the design industry still seems unable to fully understand the subsequent impact of design decisions. In an age where the rising cost of resource and increasing nervousness around security of supply of these raw materials is affecting business decisions and where 80% of the environmental impact of products is pre-determined at concept design stage this surely needs attention.

By Sophie Thomas, Co-Director of Design, RSA

With thanks to MA Culture, Materials & Design, UCL